In my previous post I discussed how pressing “reset” on drafting my new fantasy novel Legacy of Iron was the right decision for the project.

I’m now about 3 months into the writing process for “draft 1, version 2” (that won’t get confusing!) of Legacy of Iron. Admittedly this is a slower pace than I usually try to keep to. Usually when drafting I go by Stephen King’s advice in On Writing that “the first draft… should take no more than a season.” This is because sadly the writing process has had to take a bit of a back seat to other “real world” priorities, but also because I am fully content in taking my time with this book as I think a “low and slow” writing period will result in a cleaner draft and, one hopes, less editing to perform later.

For my last few projects I have been a pretty key adherent to the Five Commandments of Story structure, which are thusly:

- Inciting Incident

- Progressive Complication

- Crisis

- Climax

- Resolution

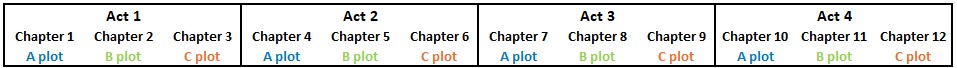

I refer to these categories as the “acts” for my stories, so I use the Five Commandments as a basis for a five-act story.

In my work on Nightmare Tenant and later Price War and Price War: The Colour of Money I have used this structure to great effect. As discussed previously I have spent more time than on any previous project in the outlining phase, I have a detailed backstory and worldbuilding document which has allowed me to be considerably more detailed in the plot of the actual novel. Usually my books have a primary “A plot” and between 1-3 alternative “plots”. To call these “plots” is perhaps not entirely true; they are “points of view” that I tell the story though. Each point-of-view navigates each act, so each point-of-view will go through their own five-act story and it is how these intermingle and dynamically affect each other that provides the core of the story.

I was considerably more careful and thoughtful in creating the plans for each of the five acts and what events take place to each point-of-view to “fill in” each of those acts. I’ve been surprised by how some points-of-view seem to have more events on each act, and in a positive way. I feel that this approach allows me to richly tell the story through the points of view of four characters – some good, some bad, some… well you’ll find out!

However, in dealing with a story of greater scope I feel I have had to adjust how I administer this project. So far I’m about 80% through the “inciting incident” where a lot of the initial worldbuilding and introduction to the shenanigans that will dominate events later in the book takes place.

In previous projects I would assign (or sprinkle) the chapters in a rotation and write linearly. Usually in the early planning stages this would be fairly arbitrary in “oh, chapter 6 is a B-plot chapter, then we go to a C-plot chapter in chapter 7 and let’s catch up with A-plot again in chapter 8”. This would usually be the final running order of the chapters, with breaks to alternate points of view that you would expect in the finished book (for flow/pacing). This diagram I feel illustrates it:

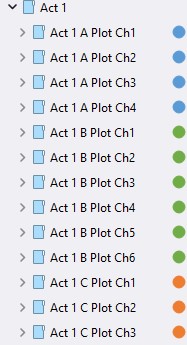

However, with Legacy of Iron, I have decided to write all the chapters for each point-of-view linearly. My intention is to then “re-order” the chapters into the final running order later when I am ready to assemble the draft into its final form. So at the moment I’m writing all the chapters for the “A-plot” sequentially, so I have the whole of the “A-plot” side of Act 1 written, the moving to the “B-plot” etc. My plan is to then rearrange the chapters into the final running order to consider pace and point of view shifts that will both flow better and take place sequentially.

Why am I doing it this way? I feel it’s easier to write all the chapters for each point of view in one go in order. This way I don’t have to “head hop” between characters and I can continue without having to “find my place” again when rejoining a particular plot thread, especially as each plot thread for the first act (in this example) takes place over several days with various events. I can focus on one point of view and dedicate my energy to that and get that finished, then move onto the next point of view. When I have completed each of the five acts to cover all four points-of-view I can then spend time working out a better and more pleasing pacing order, while maintaining a cohesive narrative flow (as some of the chapters I’m writing take place “back in time”, which I am trying to track a lot better, which will be helpful as there’s some pretty tight timing on some of the narrative events to keep track of and there’s being mindful that these plots are a lot of the time, at least initially, taking place at the same time).

I see this approach as a simplification of the writing process, allowing me to focus fully on each character’s perspective without the cognitive load of constantly switching ‘hats.’ For example, I’m currently working on the ‘C-plot’ for Act 1, which centres on Cardinal Thaddeus, a longstanding royal adviser whose machinations with a mysterious group of benefactors set the story in motion. By writing his chapters as a single ‘block,’ I can maintain continuity and dive deeply into his narrative. Later, I’ll intersperse these chapters throughout Act 1 to create a more dynamic, ‘cinematic’ flow, much like how a film might shift between characters’ perspectives to build tension and pacing.

Act 1 currently stands at around 45,000 words, which I acknowledge is lengthy. However, I’ve embraced the likelihood that not all of this material will make it into the final draft—and that’s perfectly fine. Writing freely at this stage is both enjoyable and productive, allowing me to create a rich ‘pool’ of content to draw from later. I’ve already skipped some planned chapters, realising they weren’t necessary; if they felt dull to write, they’d likely feel dull to read. This freedom is also encouraging a bit of experimentation, as I know I can refine and streamline during the assembly phase. Even unused chapters won’t go to waste—they might serve as companion pieces or bonus content in the future.

A key change I’ve done for writing like this is that I’ve actually abandoned traditional chapter numbers – at least, for now. I still use scene numbers which refer to my planning spreadsheet. I feel the chapter numbers are both meaningless, as “chapter 6” as I’m writing it now may not be “chapter 6” when reordered, and having them running out of order in my writing program Scrivener will be confusing and also drive me a little bit nuts, so I spent some time renumbering the chapters as you see in the image.

Act 1 A-plot Chapter 1 – this nomenclature means that this chapter is “Act 1, the A-plot, Chapter 1 of the A-plot”.

I realise this is a bit of a bold experiment and something I’ve come up mostly on the fly but already I feel this is helping me to navigate the writing process of a book as long as Legacy of Iron is likely to be. While I am mindful that extremely long books are both a bit of a fantasy “trope”, but may be difficult to edit, market and for readers to enjoy, so far I am really enjoying the writing I am doing. I feel it’s better to have written too much story than not enough and I’m not angry or upset at writing scenes/chapters I might not even publish. I’m excited to see how this book comes out and how this experiment works!

Be sure to subscribe to my monthly newsletter for more project updates!

Leave a Comment